Background and Brief Lifecycle

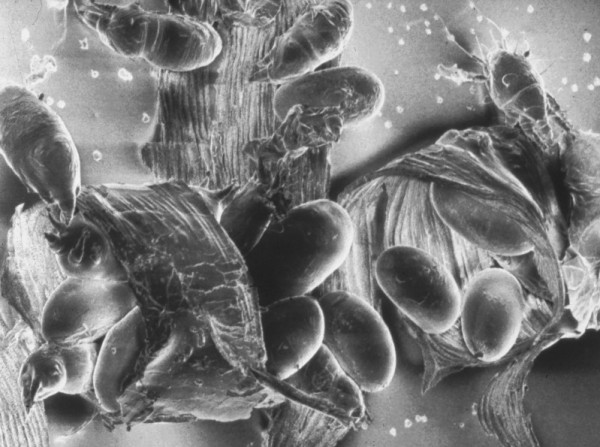

Tracheal tube blocked by Acarapis woodi and eggs

Tracheal tube blocked by Acarapis woodi and eggs

It is thought that the Tracheal mites (also known as Acarine) was a major contributory factor to the ‘Isle of Wight disease’ first seen in the early 1900s. It decimated the honey bee population, later spreading to mainland UK. In more recent times, the Tracheal mites have had a serious economic impact on the beekeeping industry in North America, after it’s introduction there in the 1980s from Mexico. However, in the UK Tracheal mite infection is not usually a serious disease, with relatively small numbers of colonies being affected.

Acarapisosis is the infestation of the breathing tubes (trachea) of the adult bee by the parasitic mite Acarapis woodi. The honey bee delivers oxygen to body tissues via diffusion through a complex system comprising of tubes called trachea and air sacs. It is in these trachea that the acarine mites reproduce and feed. Mature female mites enter the anterior thoracic spiracles of young bees (bees are only susceptible to infestation within the first nine days after emergence). The mites lay their eggs in the trachea and upon hatching the larvae begin to feed on the haemolymph (blood) of the bee. The larvae undergo several moults before reaching their adult forms and are then ready to infest new hosts.

Symptoms

In many cases bees cluster in front of the hive, appearing confused and disorientated, unable to return to the hive. Some of the bees may also display what is known as ‘K-wings’, where the rows of hooks holding the pairs of the bee’s wings together become detached. However, these abnormalities are not always seen and can be due to other factors not linked to Acarapisosis

Mite infestations may also shorten the lifespan of over-wintering bees which leads to ‘spring dwindling’ as a result of the winter bees dying early in the spring. As a consequence the expanding brood cannot be supported sufficiently by the remaining adult population, leading to the demise of the colony. It has been suggested that if the colony goes into winter with greater than a 30% infestation then the colony is unlikely to survive.

Diagnosis and Treatment

The disease can only be easily diagnosed by carrying out a dissection and microscopic examination (using a dissecting microscope with up to x40 magnification) of the primary trachea. In a healthy or un-infested bee the trachea will have a uniform, creamy-white appearance.

Healthy tracheal system in a honey bee

Healthy tracheal system in a honey bee

In infested bees the trachea will show patchy discolouration or dark staining, (melanisation, caused by mites feeding). In addition the eggs, nymphs and adult stages of the mite may also be seen in the trachea.

Acarine eggs in the tracheal tube

Acarine eggs in the tracheal tube

There are currently no approved treatments for Acarine. The best method of control available to the beekeeper is to re-queen colonies that are susceptible to the disease.

Further Information

- More information about the tracheal mite can be found in our advisory leaflet Common Pests, Diseases and Disorders of the Adult Honey Bee;

- Further information is available from the OIE Chapter on Acarapisosis.