There are several brood diseases and disorders that, although much less serious than foulbrood, are widespread. It is essential to be able to recognise these and distinguish them from foulbrood.

Sacbrood

Sacbrood virus (SBV) is a common and widespread virus across the world, and it is found throughout the UK. This virus is so common that it is likely that most beekeepers will encounter it at some point. In the UK, SBV was one of the three most common diseases found (chalkbrood and parasitic mite syndrome being the other two) during inspections performed by the NBU between 2006 and 2016. In most diseased colonies, relatively few larvae are visibly affected, and it rarely causes measurable harm.

Cause

The virus replicates in the hypopharyngeal glands of infected adult bees. It can shorten the lifespan of adult bees but causes no visible symptoms. They then secrete the virus into the food they feed to the developing larvae, which become infected when they ingest the contaminated food. Larvae are susceptible up to eight days of age. The virus prevents them from shedding their last larval cuticle (skin), causing fluid to accumulate between the body of the larva and its unshed skin, resulting in death. It does not usually cause severe colony loss.

Recognising signs of sacbrood

Sacbrood virus causes the unmistakable sign of gondola-shaped larvae protruding from their cells. Larvae that have become infected with SBV fail to pupate and die just after capping. As the virus prevents larvae from shedding their skin, their bodies fill up with fluid. If the larval remains are ruptured, the contents are a granular, brownish liquid and more-or-less watery depending on the state of decomposition of the larva.

The outer skin of affected larvae becomes thick and can be easily removed from the cell intact. It is common to find uncapped cells containing larvae that have died from sacbrood as the bees will uncap the cells and attempt to remove the diseased larvae. Often, in capped cells where a larva has died from sacbrood, the capping will be nibbled by the bees. The infected larvae lose their pearly white colour and turn yellow during the first stages of decomposition.

Transmission

The virus can be spread by adult bees through robbing, and to a lesser extent by drifting. Queens may also transfer the virus onto their offspring via their eggs, and it may be spread between bees in the colony via the faecal-oral route. The virus can remain viable in honey or pollen for a month, so it can be transmitted by the movement of frames between colonies.

Treatment

A colony should be able to handle the infection without intervention, but if the disease is persistent, there are a small number of management options available. It may help to remove most of the diseased combs and replace them with clean comb. Colonies with persistent sacbrood infections may benefit from either requeening the colony with a younger queen to break the possible transmission route of virus from queen to brood, or by caging the current queen for ten to fourteen days to stimulate a short brood break; preventing re-infection of larvae that are at the susceptible age.

Chalkbrood

Chalkbrood is a caused by a fungus called Ascosphaera apis. The fungus grows best at temperatures slightly below optimal brood rearing, which is why chalkbrood is often associated with chilled brood. Chalkbrood is fatal to infected larvae and can result in a decline in bee numbers and honey production, but it does not typically cause the demise of a colony. Chalkbrood is one of the three most prevalent diseases in the UK (the others being sacbrood and parasitic mite syndrome).

Cause

When ingested by a larva, the fungal spores germinate in the midgut and produce mycelia. 'Mycelia' is the collective term for groups of hyphae; a network of fungal threads produced by the fungi, that it uses for feeding. The mycelium is responsible for reproduction and forms fruiting bodies, which will generate more spores. The spores that germinate in the larval gut produce enzymes that damage the larva, causing it to die. The mycelia then break through the cuticle and the larva turns spongy and white, at first, then becomes hard and chalk-like.

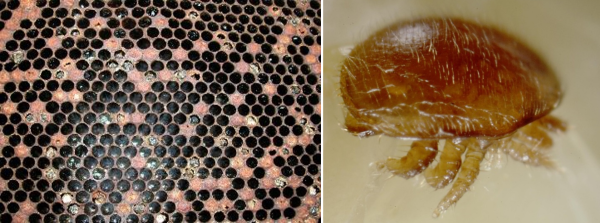

Recognising signs of chalkbrood

Chalkbrood infected larvae will initially be covered by fluffy, white fungus and then dry out and shrink down to form a distinctive ‘mummified’ chalk-like appearance. Like some other brood disorders, there may be perforated cappings. Workers will uncap and remove infected chalkbrood cells, resulting in an uneven or ‘pepperpot’ brood pattern. Infected larvae often take on the hexagonal shape of the cell itself before shrinking in size, at which point, the bees are able to remove them from the comb.

Chalkbrood mummies removed by the workers can be found on the floorboard or outside the entrance. They are distinctive but could feasibly be confused with mould. However, when rubbed between two fingers, mouldy pollen will break up easily, whereas a chalkbrood mummy will not and is hard to crush between the fingers.

Although the larvae become infected during the early stages of life, they won’t exhibit signs until just before, or up to two days after capping. Workers uncap and remove the majority of infected cells, so only a small proportion of the infection may be visible.

Transmission

Each chalkbrood mummy can produce millions of infectious spores that stick to the brood cells, hive components and adult bees. While adult honey bees are not susceptible to infection, they can transmit the pathogen within the hive and to other colonies. Food sharing between adult bees allows fungal spores to be carried by foraging bees and subsequently passed to susceptible larvae. The spores, which are highly infectious, are spread through robbing and drifting of worker bees, and via contaminated equipment or hive products such as wax, honey or pollen. Chalkbrood spores are tough and may persist in the environment for fifteen years.

Treatment

There are no specific treatments available for chalkbrood, but it is suggested that requeening from a different stock may benefit colonies suffering from repeated or severe infections, as some honey bee strains of are naturally more resistant to chalkbrood.

Management techniques to reduce infection with chalkbrood include keeping hives clean, replacing storage and brood combs at least every three years, and keeping hives well ventilated and dry. During spring and summer, enlarging the colony entrance to improve ventilation may help. While in autumn and winter, reducing the volume of the brood chamber may help control chalkbrood.

Chalkbrood spores persist particularly well in pollen; so, removal of stored pollen from infected hives and provision of a protein substitute may help reduce infection levels in an affected colony. Placing pollen traps on colonies has been found to worsen chalkbrood infections, so these should be avoided. It is also suggested that a pollen/protein deficit could aggravate the condition. Spores are very persistent in the environment, so it is important to use clean equipment and not to transfer material between colonies if infection is present. Chalkbrood spores may be found in pollen, honey and wax and can be transmitted to other colonies by transfer of these products, so this should be avoided.

Parasitic mite syndrome

Parasitic mite syndrome is caused by the mite, Varroa destructor, in combination with the virus, deformed wing virus (DWV). Parasitic mite syndrome, also known as varroosis, is one of the three most prevalent diseases in the UK (the others being sacbrood and chalkbrood).

Cause

When Varroa feeds on developing brood, it acts as a vector for transmission of DWV. Individual bees infested with Varroa during their development usually survive to emergence, but will suffer from physiological damage as adults, such as a shorter lifespan, reduced weight upon emergence, and an increased susceptibility to infections.

As colonies become more heavily infested with mites, levels of DWV increase in the colony. At high levels, DWV kills pupae and causes deformed wings in adult bees. Signs of this condition indicates a terminal decline of the colony.

Recognising signs of parasitic mite syndrome

Due to the loss of pupae, an uneven, ‘pepperpot’ brood pattern will occur. As brood dies, there may be an insufficient number of young bees coming through to tend the brood, so neglected brood may become apparent. There may also be a lack of eggs and early brood stages.

Bees with deformed wings and shortened abdomens will become more common as the virus levels increase and there will be numerous Varroa mites observed on adult bees, on worker and drone pupae and on the hive floor.

Brood abnormalities such as bald brood, patches of neglected and dead ‘emerging’ brood, often discoloured brown and partly cannibalised by the bees will be apparent.

Treatment

Treatment and prevention of parasitic mite syndrome involves year-round management of Varroa mites. There are treatments and husbandry techniques that are effective at keeping mite levels below a threshold where it can damage colonies. For more comprehensive information about parasitic mite syndrome, and how to prevent it, please read our advisory leaflet, 'Managing Varroa’.

Other brood disorders

For information on other brood diseases and disorders, please refer to our advisory leaflet ‘Foulbrood disease of honey bees and other common brood disorders’